What's that metal baffle doing on my bocal and wing joint?

It's a lefreQue Sound Bridge!

For hundreds of years, instrument manufacturers have broken the bassoon into several parts to make it more compact for carrying and to keep it out of harm's way. I've certainly never thought about what acoustical trade-offs occur when you cut up the body of the instrument into several parts.

However, it stands to reason that some resonance must be lost when an integral piece of wood is sectioned off. Especially when the sections are joined by tenons with cork or string wrapping.

In the chart below (from Maarten Vonk's bassoon website), you can see the relative speed of vibration for various materials. Cork is on the slow end. Thus, it is often used to insulate or dampen vibrations in a room, for instance. Cork is a great material for maintaining a secure, tight seal between joints, but not the ideal substance for the resonance of a musical instrument.

Air 330 m/s

Glue less than 50 m/sCork less than 500 m/s

Solder (lead) 1260 m/s

Wood soft/ hard 1500 / 4000 m/s

Brass 3600 m/s

Gold 4700 m/s

The concept behind the lefreQue Sound Bridge is to link the resonance in the individual joints of the body of the instrument by placing a bridge between them.

The bridges are easy to install and take off. They are not permanent and do not require a repair technician to modify your instrument.

Research:

Before purchasing, I did some investigating with other bassoonists, repair technicians and by viewing various Internet sources.

There is a lefreQue YouTube channel but no bassoon demos at this point.

West Virginia University Bassoon Professor, Lynn Hileman has written an informative blog about her trial of the sound bridges.

Photos of them in use on bassoons show various methods of deployment.

Trials:

I have only tried the bocal/wing bridge (known as the Double Reed model) and the bridge for the long/bell juncture. I tried the various materials available, too -- sterling silver, solid silver, red brass, etc.

I tried them on my students' bassoons and we probed them in our bassoon section.

The results were surprisingly variable. While my tests were by no means scientific, I noticed a wide variety in result (ranging from no audible difference to near life-changing difference).

What I've come away with from months of testing is that every bassoonist needs to decide for him/herself if these bridges do anything at all, and if so, which ones, and how best to deploy them on your instrument.

Ways to Try:

Here are some ways I tried. My conclusions are based upon what worked for me, so try them yourself. In trying yourself, be sure to investigate all the different materials and ways to deploy them. I've heard from other bassoonists who use these very differently from me and are quite satisfied!

1. Which bridges?

Some bassoonists are "fully lefreQued"! They use the bridges as a system. However, these little baffles are very expensive, so I would suggest trying one bridge at a time to see if a particular bridge is really adding anything at all.

My trials show that the only bridge that added any resonance for me was the Double Reed bridge -- or the one that bridges the wing joint and bocal. The only other one that had even a hint of added resonance was the long/bell bridge -- but not enough to justify a purchase.

2. Which material?

I tried the various materials (a lot like shopping for bocals!) and found the solid silver added the most resonance and gave the best sound.

3. How to deploy?

This may be the area that needs the most investigation. There seems to be no standard way to apply these, and for me, some of the most recommended ways didn't work very well.

The bridges seem to be very finicky if not assembled and positioned just right. Some people notice a fuzziness or buzzing coming from them at times. Like what you may experience from a sympathetic vibration coming from the body lock.

If you experience this buzzing, before rejecting a lefreQue for your bassoon, try re-positioning the bridge on the joint and make sure the two bridges are perfectly aligned one on top of the other with no overlap.

|

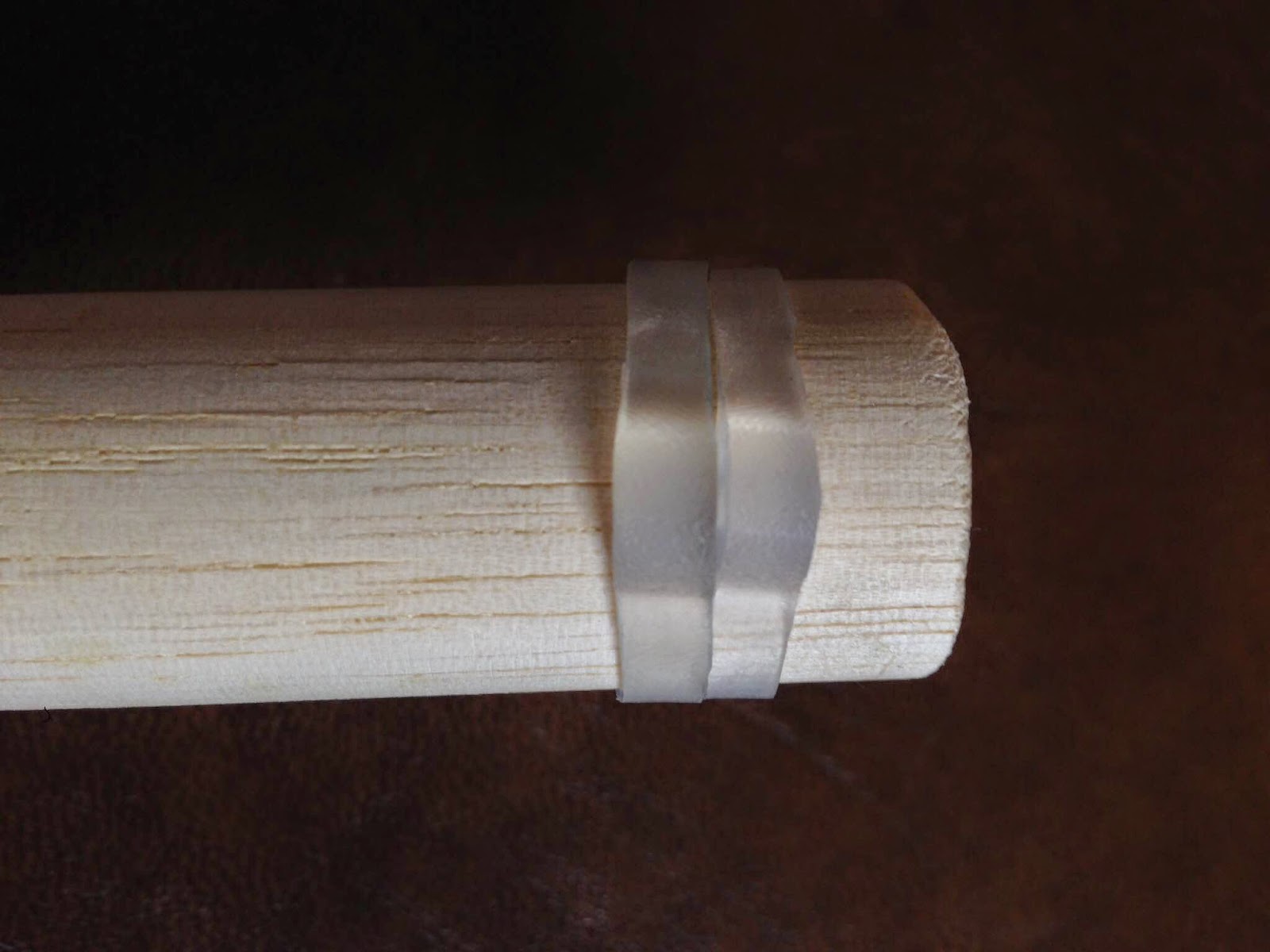

| Overlapping bridges |

Tension from the silicon band may cause the bridges to slip apart slightly when you put them on. Keeping one exactly on top of the other will decrease damping caused by metal touching metal (which may also cause some of the buzzing).

Each lefreQue comes with a set of two bridges. They should be used together, with the smooth bridge on the bottom and the "bumpy" one on top.

|

| Top side |

|

| Underside |

These bridges are not interchangeable. My trial with the bridge with the bumps placed on top of the smooth bridge produced more resonance than vice versa.

In the photos you can see how the two differ. The bridge on the left side is the bridge that contacts the body of the bassoon. It helps the body resonance jump from joint to joint.

The bridge on the right has little bumps that act as feet. This is the bridge that goes on top. The feet keep the bridge from completely contacting the bottom bridge and dampening its resonance. Originally, lefreQues were sold as single bridges. However, it was discovered that pairing each bridge with another one allowed for more resonance, as the lower bridge was not dampened by the fastening bands.

The tapers of the bridges are purposeful, with a more sharp taper at one end for each. This sharper taper is made to help the fit against the bocal, whereas the taper at the bottom better fits the circumference of the wing top band.

|

| Taper |

|

| Fit against bocal and wing |

How to attach?

Photos I viewed showed a few different ways of attaching the bridges. Here are the two most common ways:

|

| Bound at feet |

|

| Bound at middle |

You should try each way to see which produces the best result. I found a pretty big difference between the two, with the fitting the silicon band over the middle yielding the best resonance and sound.

I've thought a little about the use of silicon (also an insulator, not a very good material for carrying vibration). I wonder if a metal coil spring or something that also transmits vibration well might be a better agent for attaching these bridges?

The lefreQue company offers a few different kinds of bands. Indeed the package includes a veritable smorgasbord of bands. It's not clear there is one recommended way to attach as well!

How much tension?

Along with how to attach, I've wondered about the amount of tension placed on the bridges by the attaching bands. Too much could dampen the bridges' resonance, too little could add a buzzing sound.

I found a good amount of tension by accident. I lost the original band sent with my bridges. Upon obtaining a new one, I noticed that it was wider and not as big in circumference as the old one. the fit was much more tight than the old one. An upgrade?

After trying it, I thought the new band inhibited some of the resonance I was getting with the old one. To reduce the tension and, hopefully, free up some of the resonance, I cut the band's width in half. A more narrow band would be more elastic and free.

|

| Original, cut |

|

| New width |

Where to position?

Another variable in deploying these things is exactly how to position them. Here again, different positioning yielded different results.

Here are the ways I tried with the bocal/wing bridges:

|

| Under the post |

However, on my bassoon, this necessitated placing the band across the lower part of the bridge. This placed greater tension on the feet at the bottom of the bridges and very little on the top feet. There was a tendency for buzzing from the top and they were more prone to slipping out of place.

Moving the bridges down so the band could fit across the middle of them (near the trademark) caused the bottom bridge to contact the metal band at the top of the wing joint, resulting in a loss of resonance.

The best position for the band was fitting it around the very top of the wing joint metal band. It's best to put the band on before you insert the bocal. This makes it easier and safer to move or adjust the band if needed. The band is thin enough that it should fit between the wing and long joint without pushing the joints apart.

|

| Best band position |

Where, exactly?

|

| Front |

|

| Back |

The Bulge

One last thing I tried was putting the band on with the fat bulge over the bridges vs. rotating the band so the bulge is on the opposite side of the joint from the bridge. The sound was better with the bulge over the bridge. This is nice, because the bulge provides a nice, easy spot for your fingers to grab onto when removing the band. The bulge needs to be positioned exactly in the middle of the bridge's width for best resonance.

| |||||

| Bulge over bridge |

The lefreQue Sound Bridge provided a noticeable improvement in the resonance of my bassoon. It also helped some of the other instruments I tried it on, but not every bassoon showed improvement.

Attention to how the bridges are deployed, which ones are used, which material is best, how to attach them, tension of the band and where to place them on the body of the bassoon are important details you should explore when trying these bridges out.

.jpg)

(2).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)